By: David Renton

London: Unkant Publishers, 2013, 167 pp., $14

The dramatic implosion of the Socialist Workers Party (U.K.) has provoked an outpouring of analysis, debate, and sectarian invective, most of which has appeared online rather than in print. Socialist Unity, Weekly Worker, Soviet Goon Boy, and Links: International Journal of Socialist Renewal have all published exposés and polemics on the party’s shameful mishandling of accusations of rape and sexual predation on the part of a leading member, who is referred to as “Comrade Delta” in party documents. The story received prominent coverage in national newspapers, such as the Guardian and the Daily Mail, as well as on left-wing blogs. Within a matter of months, the resulting fallout had generated an exodus of hundreds of members, along with ongoing rows over the SWP’s internal regime, political strategy, and relationship to the rest of the left.

As a consequence of its history as a campaigning organization around such issues as labor rights, immigrant rights, and anti-fascism, the SWP often claims that it “punches above its weight.” But the Delta debacle has substantially tarnished the party’s reputation. The issues at stake include not only the shortcomings of the SWP’s disciplinary procedures, and the persistence of sexist attitudes and myths about rape, but also the strengths and weaknesses of the International Socialist tradition and the relevance of the democratic centralist model of political organization in an era of globalization, social fragmentation, and the Internet. Comrade Delta may have resigned from the organization in the summer of 2013, but the larger controversy rages on.

SWP leaders and critics alike regularly invoke “the IS tradition” in defense of their views. The phrase refers to the ideas and practices associated with the political tendency built by Tony Cliff and his cothinkers in Britain and elsewhere after World War II. Cliff and others split from orthodox Trotskyism to develop a revolutionary current that viewed the long postwar boom as a product of military spending and the Soviet bloc as state capitalist. Having started out with a couple of dozen supporters at the end of the 1940s, the Cliff group could plausibly describe itself as “the world’s smallest mass party” by the 1980s. By the time that Cliff passed away in 2000, the SWP had decisively outpaced its rivals on the British left and established a network of like-minded groups in a couple of dozen countries. Over the past decade, however, the party has undergone a series of faction fights and splits, with further bloodletting to come. Ian Birchall, a veteran member of the SWP and its predecessor, the International Socialists, recently published a thoroughly-researched biography of Tony Cliff that memorably captures Cliff’s eclectic political methods and engaging personal style. It is indicative of the depth of the current crisis that Birchall, along with many other longtime cadre, have attached their names to severely critical opposition documents. (My favorable review of Birchall’s book appeared in NP #52; I was less impressed by Cliff’s autobiography, which I reviewed for NP #32.)

The first book to address the implosion is David Renton’s Socialism from Below, available from either amazon.com or the publisher’s website. Other tracts and memoirs will presumably follow in its wake. Renton, who joined the party in the 1990s, is an attorney who lives and works in London. A historian by training, he is the author of numerous books, including a biography of C.L.R. James, a study of the British Communist Party, and a history of the Anti-Nazi League. His latest project consists of nearly two-dozen essays culled from his blog, Lives; Running, on various aspects of IS/SWP history and culture. Insightful, humane, and crisply written, Renton’s posts from the past couple of years make for interesting reading. As a high-profile member of the opposition, his blog has become a go-to place for late-breaking information on the party’s crisis. Judging from recent posts he may be on the verge of tearing up his membership card. The ranks of embittered former dues payers has always been larger than the network of loyal SWP supporters and members, but lately the ratio between the two seems to be growing wider.

While Socialism from Below addresses a variety of topics, from deindustrialization and public sector unionism to anti-fascist organizing and socialist morality, the book is centrally concerned with three questions. The first has to do with the leadership’s botched response to the formal complaints advanced by the two women who charged Comrade Delta with in one case rape and in the other persistent sexual harassment, as well as similar charges raised by an undisclosed number of women against less prominent members of the organization. Drawing on his experience as a labor lawyer, as well as on general feminist principles, Renton offers a number of suggestions for how the group might have responded to these allegations. In an essay titled “The Missing Letter,” he offers a template for a full-throated public apology that is yet to be written:

For a long time, we thought that if we tried hard enough to pretend that there was no problem, it would go away. It has not. We now realize that this stain will not be removed unless the party undergoes a serious, and systematic, period of reform. For this reason we have decided to: Apologize to the women who put in complaints…. Suspend from membership of the party all individuals subject to serious sexual complaints…. Release those members of the organization from full-time roles who have been exhausted by the experience of defending the indefensible…. Elect a new Central Committee, Disputes Committee and National Committee…. Begin a discussion within and outside the organization as to what it was about our procedures that enabled us to continue on such a destructive path for so long…. Begin a second discussion within and outside the organization as to how we can learn from the contemporary women’s movement…. Make the party transparent by publishing in future a public note of all meetings of all our elected committees.

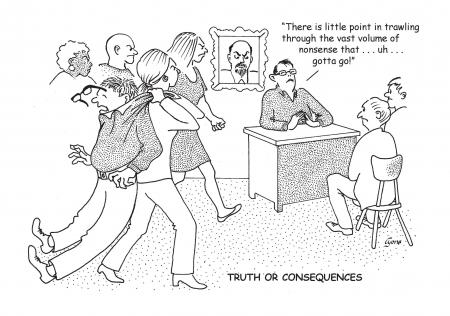

It is instructive to compare the ambitious proposals and contrite tone offered in Renton’s “missing letter” to the rather lawyerly gloss provided by Alex Callinicos and Charlie Kimber in their official statement on “The Politics of the SWP Crisis” that was recently posted on the International Socialism website:

Controversy over the case then became surrounded by a fog of gossip, innuendo, distortion and plain lies—all perpetuated on the internet and in the mainstream media, and reinforced by the shocking willingness of others on the left to believe, without any knowledge of the facts, the worst about the SWP. There is little point in trawling through the vast volume of nonsense that has been written about the case, and in any case we are constrained by the obligation of confidentiality towards the parties involved that others have so shamefully ignored.

As Renton himself has pointed out, the very phrase “the case” disguises the fact that more than one woman stepped forward to file a complaint against Comrade Delta, and that on at least a couple of occasions the party’s Disputes Committee took on unrelated cases that it was in no way equipped or qualified to handle. Callinicos and Kimber reluctantly accept that mistakes were made (“no one in the SWP leadership thinks that, with the benefit of hindsight, we would address the issue in exactly the same way”), but nevertheless insist that the time has come to “move forward.” From the outside, it is difficult to see how the organization can push on without jettisoning either its heterodox minority or its stale bureaucratic reflexes.

Speaking of bureaucracy, the second topic that Renton tackles is the question of democracy and leftist organization. As he recognizes, developing genuinely democratic structures and practices is a challenge that faces a variety of institutions, from trade union locals and single-issue campaigns to food co-ops and feminist magazines. Rigid hierarchies, self-selected cliques, and top-down command structures are recurrent problems for all kinds of formations, not just soi-disant vanguard parties. Renton’s initial effort to distill his own vision of “Democracy in a Small Party” is almost haiku-like in its brevity. The entire essay, in fact, consists of five short points:

- The determined obsolescence of leadership roles

- Having the politics to comprehend which decisions are suitable for majority decisions and which are not

- Avoiding front-ism

- Full exchange of information

- Maximizing opportunities to contribute

Renton helpfully expands on these compact formulations in subsequent essays, but the distinctively libertarian vision—in the English sense—that they express is never more aptly summarized than it is here. As he rightly points out in a concluding essay titled “Our Goal is Democracy,” “nobody wants to be ordered around anymore; the method of command just doesn’t work.” The book closes on a suitably rousing note:

Democracy begins with the way in which we speak to ourselves; in that moment of self-realization that no one is better than you, and you are not better than anyone else. Democracy begins with teaching others to address each other and you with respect. Democracy begins with regime change at home.

With its pointed reference to “regime change at home,” it seems unlikely that this essay, or others like it, will endear Renton to his own Central Committee. But then again, Renton doesn’t seem to care what Kimber, Callinicos, and their colleagues think, either about his criticisms or his libertarian-socialist ideals. As it happens, in recent weeks he’s been posting long excerpts on his blog from back issues of Women’s Voice, the socialist-feminist magazine that the party sponsored (and eventually closed down) between 1972 and 1982. This will no doubt be seen by the apparatus as yet another provocation.

All of this raises the obvious question of why Renton remains, for the time being at least, a member of a Leninist sect, imploding or otherwise. Why doesn’t he just quit? The answer has to do with the enduring appeal of the very “IS tradition” that Callinicos and other party leaders, as well as dissidents like Renton and Birchall, seek to defend. The book’s final topic is thus this laudable but deeply problematic tradition, which (as the book’s subtitle indicates) Renton quite reasonably regards as “unfinished.” In making the case for the contributions of somewhat neglected figures from the group’s halcyon days of the 1960s and 1970s, including David Widgery, Peter Sedgwick, Michael Kidron, and Alasdair MacIntyre, Renton draws an implicit and frankly discouraging contrast between the intellectual ferment of this earlier period and the rather humdrum output of today’s leading post-Trotskyists. Anyone with an interest in leftist intellectual history will find valuable material in these well-crafted biographical essays, which were written with the current crisis in mind but with one eye on the longer view.

Leave a Reply