I attended an event for the 50th anniversary of Malcolm X’s assassination that was held in the same room where the visionary leader was murdered. The commemoration, aptly titled “I LOVE MALCOLM—A Legacy of Love and Liberation,” celebrated his lifework and highlighted the struggles to be undertaken for the future liberation of black America and other oppressed peoples.

I attended an event for the 50th anniversary of Malcolm X’s assassination that was held in the same room where the visionary leader was murdered. The commemoration, aptly titled “I LOVE MALCOLM—A Legacy of Love and Liberation,” celebrated his lifework and highlighted the struggles to be undertaken for the future liberation of black America and other oppressed peoples.

Several hundred people—of all hues, and fully representing each generation—packed the room, perched on black folding chairs. Dozens more crammed the sides and back of the room to listen to the public intellectual and historian Tariq Ali recall Malcolm X’s famous 1964 speech and debate at Oxford University. They listened, too, as poet and political dissident Sonia Sanchez recollected the magnetic charm of Malcolm, and his infusion of love into his philosophy. The collective mood in the room gradually shifted from a buzzing expectancy to resolute conviction. While the event itself was geared toward reflection on Malcolm X’s life, many, if not most, of the attendees were searching for answers to this political moment in the struggle for black liberation in the wake of Ferguson and other absurd injustices. As I ruminated on the significance of Malcolm, the inescapable question kept prodding me: What would Malcolm say or do if he lived to see this nascent #BlackLivesMatter movement?

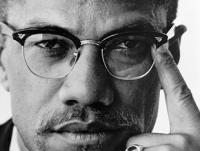

In the 1950s and 1960s, Malcolm X articulated the simmering angst of black America, weighed down by white supremacist imagery and institutional oppression, into boiling rage demanding urgent attention to the unfathomable contradictions of life for African Americans. Yet, decades later the United States remains a white supremacist country. And so, Malcolm X’s political thought and revolutionary symbolism continue to be relevant insofar as black Americans continue to be oppressed.

Half a century after Malcolm X’s assassination, this nation has produced no comparable political or intellectual leader. The literal life-and-death circumstances of too many blacks in this country, exemplified in heinous police killings of Eric Garner, Akai Gurley, Tamir Rice, and Michael Brown, demand an inspection of what constituted this irreverent spokesperson for the plight of black humanity.

Malcolm X was an organic intellectual who took the world by storm and whose words continue to reverberate to dispossessed peoples worldwide. His statement, “Our objective is complete freedom, complete justice, complete equality, by any means necessary,” endures as a rallying cry for activists. His condemnation of the inhumane conditions suffered daily by black people was novel in that it both critiqued the structures that afflicted the black masses as well as blacks themselves for their complicity in their victimization. Malcolm challenged black people as agents who have been victimized, not mere victims yearning for salvation (his scathing rejection of the Christian Church as too passive and concerned with the afterlife made him both compelling and alarming to many people inside and outside of the black community). Liberals, in their post-modern push for cultural relativism, have been paralyzed to confront the psychological effects that centuries of terrorism, exclusion, and devaluation have had on black society and culture. So it has become taboo to discuss these psychological and cultural maladies affecting black America unless one is a neoconservative who ignores all structural barriers to black fulfillment. But Malcolm was able to speak directly to African Americans and affirm their blackness, if only momentarily, and ignite outrage toward the source of their internal ills: the white supremacist power structure, which they could viscerally understand.

Malcolm also challenged the racist power structure by striking it with techniques that transcended established parameters of debate on race relations. He was incensed at the iniquitous treatment of his people and let that be known on national and local television and radio programs. He refused to acquiesce to complacency, and broke all taboos about how forthright one could be in discussing race relations. In contrast to so many African-American leaders, Malcolm was not a careerist, nor was he remotely interested in attaining more status or power for himself.

For radical and progressive activists today, it is important to consider the role of Malcolm’s militant stance in the context of the civil rights movement. The rhetoric of black nationalism pushed civil rights leaders to the left, and also made reformist proposals more palatable to the established power structure. Whenever the boundaries of political debate are expanded to include more radical ideology, there is a shift in what is considered moderate. The sharpness of Malcolm’s critique was enhanced in 1964 as he converted to Orthodox Islam after traveling throughout the Middle East and Africa. (It should be noted that Malcolm had little to say on the undemocratic and often patriarchal nature of many of the countries he visited. The broad acceptance and affirmation of him as a full human by Middle Eastern whites may have eclipsed those shortcomings, or perhaps Malcolm was too cynical about the prospects for democracy in America to be moved to criticize these nations.) This evolution of Malcolm’s thought, which included the appreciation of multiracial coalitions and the international scope of racism, completed a rift that grew between him and the Nation of Islam. But it was primarily because of Malcolm X’s rhetorical abilities and piercing insights into the plight of black people that the Nation of Islam was able to grow from an obscure sect of several hundred into a national force with tens of thousands of members. This development, and the later creation of Malcolm’s own Organization for Afro-American Unity, frightened politicians enough that they preferred to deal with the peaceful and legislatively minded Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., backed by reformist organizations such as the NAACP and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

So we leftists need to remember Malcolm X today because so many of the “leaders” and organizations purporting to represent the interests of African Americans and other minorities have thoroughly sold out. The veneer of minority representation is easily captured by superficial rhetoric, but the system is impervious to fundamental challenges when black intellectual leaders and politicians become ingrained in the very establishment from which blacks seek relief. Despite his popularity among the common black person of his time, both nationally and internationally, Malcolm remained poor until his death, and exemplified uncompromising indignation toward a corrupt political and media environment.

Many of his proposals, which he never was able to delineate due to his early death, are still relevant to radical political strategy in the present. Namely, the self-defense of African Americans against the wholesale slaughter by occupying police forces has to be a starting point for political organizing in black and brown communities. Self-defense need not mean arming communities of color—the outright murder of too many Black Panthers by the FBI testifies to the state’s monopoly on violence—because political resistance and proactive organizing can increase safety and accountability more so than a futile arms race with militarized police forces. The ceaseless organizing and protesting in Ferguson, culminating in the attorney general’s indictment of Ferguson’s entire police force for systemic racism and exploitation of the black population, demonstrates the capacity of black communities to advocate on their own behalf and get tangible results in the struggle against police barbarism.

Malcolm also suggested that the political blueprint for transforming our racist society lay at the international level, wherein African and Asian world leaders would be sympathetic to the case of human rights violations perpetrated by the United States government against African Americans. He thought institutions such as the United Nations or the Organization of African Unity could be allies in the struggle for black freedom in the states. While the efficacy of the United Nations to deal with structural barriers in the United States seems questionable, the objective of creating international coalitions based on mutual self-interest against the global minority of Western, white, capitalist countries seems promising.

Another integral idea Malcolm envisaged was independent ownership of black businesses in black communities. He contrasted the devastating transfer of wealth out of the black community with the beneficial circulation of money within the Jewish community. The basic principle is that blacks should patronize black-owned businesses, that those businesses should employ members of the community, and so on. While this may reflect the visions many conservatives would offer to this struggle, it is worth noting that liberal doctrines alone have done very little for the positions of most blacks since the 1960s. Seizing economic power and transcending liberal-conservative dichotomies is the only viable option toward alleviating racial inequality. The other side of black-owned business is black-controlled political organizations; even after his opening to multiracial alliances, Malcolm believed that black political autonomy could not be realized so long as these organizations were funded (or staffed) by white philanthropists.

A final idea of Malcolm’s that remains especially appealing to radical sentiments today is the establishment of a united front to bring to bear the collective power of African Americans against white supremacy in America and abroad. Although he obviously did not live to see such an organization, Malcolm imagined that his new Organization for Afro-American Unity could unite blacks of the middle and working class, liberal and radical, academic and organic, against the constant war of visual devaluation, institutional discrimination, and cultural denigration faced by all blacks. Such an organization, he envisioned, once constituted, could legitimately form coalitions with organizational allies from other races to tackle an establishment that fails to value life, especially black life.

For black Americans and their allies today, #BlackLivesMatter has shown the potency of collective fervor to affect the actual operations of oppressive institutions. The spirit of Malcolm X persists in the defiance of these activists who refuse to accept the absurd predicament of life for most African Americans. We have seen that months of consistent protests brought to bear enough political pressure to expel key Ferguson police and civilian power brokers.

Let me be clear: The spectacle will not replace the substantial. Sensational news stories favoring liberation principles have an expiration date, and with them the expanded political power that is yielded to advocates for racial justice. We can win the war on the message and still remain powerless if we fail to organize the political and economic power that has been activated by the publicized atrocities committed last summer in Ferguson, Staten Island, and across the country. The lesson to take away from Malcolm’s life is not simply to be outraged by the deplorable treatment (from state-sanctioned murder to world-leading incarceration rates) of working-class African Americans. The lesson is to channel that rage into a consistent effort to organize, awaken others, and speak candidly about vital issues in our communities.

Leave a Reply