"Someone threw a rock, and like monkeys in a zoo, they all started throwing rocks.” This remark was not made in the wake of the Michael Brown grand jury verdict. It was the account of Chief William Parker, spoken decades before and 1,500 miles away, on the unrest of the 1965 Watts Riots. However, for those who have been attuned to the news in the past months, Parker’s remark is eerily similar to that of a Ferguson police officer, who labeled the protesters as “f–king animals,” an appalling racial epithet.

"Someone threw a rock, and like monkeys in a zoo, they all started throwing rocks.” This remark was not made in the wake of the Michael Brown grand jury verdict. It was the account of Chief William Parker, spoken decades before and 1,500 miles away, on the unrest of the 1965 Watts Riots. However, for those who have been attuned to the news in the past months, Parker’s remark is eerily similar to that of a Ferguson police officer, who labeled the protesters as “f–king animals,” an appalling racial epithet.

Ten years prior to the Watts Riots, brave Rosa Parks refused to give up her bus seat. Yet blacks still dwelled in misery as the most indigent sector of American society, frequently humiliated in their encounters with police. The California state government had recently passed Proposition 14, an initiative supported by California real estate interests that gutted the groundbreaking housing provisions of the Rumford Fair Housing Act of 1963. The situation reached a breaking point for thousands of black youth. They responded in the only immediate manner available to them—rebellion.

The violence in the streets of Los Angeles provoked a severe backlash in the halls of Washington DC and in the offices of America’s media conglomerates. President Johnson denounced the riot as an attack on the country. Even moderate civil rights leaders like NAACP General Secretary Roy Wilkins called on police to “put down [the riot] with all necessary force.” Those in power—white politicians representing the ruling class—could not comprehend why young Negroes would start burning cars and attacking cops.

For milquetoast liberal whites concerned with what we now call “respectability politics,” these actions were appalling. White audiences with a paternalistic attitude towards blacks, watching TV, were shocked at the transformation occurring before their eyes. They were used to the “good Negro” who marched peacefully and sat indignantly, withholding anger and maintaining a moral righteousness in the face of brutality. According to one view, these nonviolent methods were the manner by which blacks would be incorporated into the system; it was their ladder into the elite structures of American society, which abounded with wealth and opportunity. But the era of purely pacifist protest was drawing to a close.

After witnessing the brutality displayed against the “polite” civil rights activists in the South, after experiencing the dynamic, institutional racism in their ghettos, and after being forcibly compelled to serve a white-dominated country in wars against other oppressed peoples across the globe, the youth of the 1960s no longer found appropriate the “respectable” approach pioneered by Booker T. Washington and later partially adopted by other moderate civil rights leaders. The litigation, boycotts, and marches did not satiate their desire for liberation. They instead looked to leaders like Malcolm X, Kwame Touré (originally Stokely Carmichael), and H. Rap Brown, who were bold in their statements and often fearless in their actions. They did not seek the approval of the political establishment, nor did they consult the upper echelon of black America. They acted. The creed of the Watts generation was summarized by Malcolm X in 1964: “Nobody can give you freedom. Nobody can give you equality or justice or anything. If you’re a man, you take it.”

Black Power activist Kwame Touré hinted at the differences between the agrarian South and industrial North and the consequences of those differences for the civil rights movement in Black Power: The Politics of Liberation (1967), when he wrote that racism “is both overt and covert. It takes two, closely related forms: individual whites acting against individual blacks, and acts by the total white community against the black community. The second type is less overt, far more subtle … [and] originates in the operation of established and respected forces in the society.” Though the Ku Klux Klan was tolerated, even encouraged, by southern governments, it was not a genuinely legal institution; it was a gang of vigilantes. Therefore its terroristic violence was met with horror by northern liberals. Likewise, the violence meted out by southern police (sometimes Klan members themselves) in response to nonviolent protest was effectively in violation of federal legislation stemming all the way back to Reconstruction-era Enforcement Acts and was similarly condemned. But the strategy of nonviolent marches and demonstrations undertaken in Selma and Birmingham was not suitable to the predicament that blacks faced in urban industrial areas. The racism that existed in areas like Watts was institutionalized in a different way. Economic inequality, severe poverty, and economic barriers to public accommodations were systemic problems that did not involve the burning of a cross. The physical brutality of the Klan in the South was replicated “legally” by the batons and guns of urban police officers.

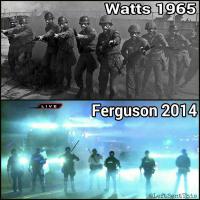

The Watts revolt happened in 1965, but what occurred back then is being echoed by developments today. Over the past few months, protests have flared up across the United States—some peaceful, some violent. Unfortunately, the clichéd saying of “the more things change, the more they stay the same” still applies. The scenes of burning cars and smashed windows in Ferguson, reminiscent of those in Watts 50 years ago, have incensed today’s establishment officials and icons. President Obama stated he had “no sympathy” for those causing “violence”—though of course he has sympathy for corporations and bankers eviscerating working-class communities across the country, black, brown, and white. The black elite’s embrace of respectability politics is as centrally important as ever.

Furthermore, in absorbing the constant flow of images and footage of protests from all over the country, one can easily submit to labeling young blacks out in the streets as simply “rioting.” However, as I personally witnessed and saw in countless hours of footage, a genuine rebellion seemed to be fomenting. Consciousness was raised to an unprecedented level, and people acted—albeit interspersed with occasional acts of property damage—yet the core of the issue is that a multitude of people were discontent. Millions declared that they would not submit to or acquiesce in today’s society. Our voices and our feet demonstrated that there was the beginning of a legitimate social uproar. Again individuals, particularly poor black youth, resorted to immediate means of expressing frustration. We understood that as Kwame Touré said, “There is a higher law than the law of government. That’s the law of conscience.” People broke the law, justifiably and unjustifiably. However, the critical point is that these actions were primarily in response to the oppression and state violence experienced by so many of today’s youth. Moreover, there exists a similar dichotomy of respectability politics versus revolutionary politics in activists’ and organizers’ responses to the Ferguson uprising. Leftists began organizing campaigns, and groups that I have encountered heightened their attacks against the structural roots of oppression in contemporary society, namely policing approaches such as broken windows, as well as broader systemic problems such as capitalism in and of itself. One can even hope that genuine, independent, left-wing parties can achieve the same success in issues surrounding policing as they did regarding minimum wage (Kshama Sawant). Conversely, the establishment approach lingers on, with figures like Jesse Jackson and groups like the NAACP insisting upon reforms within the Democratic Party. Al Sharpton’s meetings with “our” president achieve little in the way of solving the multitude of problems that black and brown communities face. Our “hope and change” president has achieved little for us, despite his promises.

The United States was ostensibly founded on the ideals of “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” Our founding fathers, as the dogmatic narrative endlessly tells, revolted when the achievement of those ideals were denied to them. The Boston Tea Party is commemorated as a heroic event in American history. This act destroyed the property of the British East India Company, with estimates of $1 million in present-day damage. Our brave “heroes” violated the sanctity of private property because they believed that the Lockean principles of the social contract were violated by the British Empire. What makes this so different from the actions of the toiling masses of black youth in the urban ghettos, whose social contract with the state is violated routinely?

Those Watts fighters revolted against discrimination by the city and state governments and against the charlatans who owned the local grocery stores, which were quick to cheat a poor family of their income. Despite obvious differences in circumstances, the black establishment’s response to the rioters mimicked that of the leading “founding fathers” to the Sons of Liberty’s economically costly tea party. In response to the destruction of tea, George Washington, the iconic figure in the patriot movement, condemned the Boston Tea Party for “hurt[ing] our cause.” Such statements could have easily been issued by the more moderate leaders of the civil rights movement in response to the Watts Riot. The Sons of Liberty were simply a more radical component of the independence movement, just as the Watts protesters were in a movement that included NAACP leaders. This illustrates the blatant hypocrisy of some who are more concerned with private property than police brutality. Watts had a clear context. Those who revolted did not exist in a vacuum, but in a socioeconomic system that deprived them of their basic rights and dignity.

I want to clarify that I do not support initiating violence. I have not committed any violent acts in my participation in the protests. But I believe that if we are to achieve a radical vision of equality and justice we must recognize the roots of the problem, rather than fixating on its side effects. Ferguson was an initial reaction. Indeed, one can say it was a beneficial reaction, in that it awakened America and demystified the reality of oppression to white audiences who were in the dark. And while I am not in favor of burning down black businesses, I must sincerely ask why the sanctity of private property is deemed more important than the black and brown lives that are constantly being ruined in our cities and suburbs.

There are many similarities between the Watts and Ferguson protests. We must hesitate before quickly condemning the actions of angered, troubled individuals; we must grasp the larger picture. Instead of focusing our efforts on riot control, let us focus on attacking the inequality that produces such “riots.” When confronting the blatant hypocrisy of our supposed representatives and the media, we must remember the words of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in 1967: “I could never again raise my voice against the violence of the oppressed in the ghettos without having first spoken clearly to the greatest purveyor of violence in the world today: my own government.”

In the wake of the Watts Riots and other scenes of unrest in the 1960s, California Governor Pat Brown created a commission to study the roots of these disturbances. The commission’s findings were finalized in the McCone Report, completed in an effort to understand and reduce the potential for further riots. The report indicated that there was a “devastating spiral of failure” that existed in black America. Does this spiral still exist today? A recent Dissent magazine article was titled “50 Years Later: Poverty and the Other America.” It would not be improper for a future article to be titled “50 Years Later: the McCone Report,” in response to the protests that have arisen against the police killings of Michael Brown and Eric Garner, among too many others.

Leave a Reply