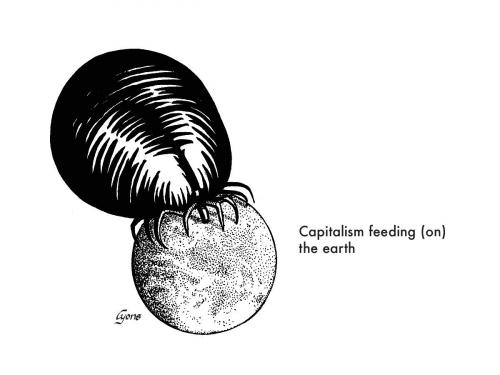

In the United States today, there is a fresh opening for progressive alliances. The various movements—Black Lives Matter, the Fight for $15, climate change, immigrant rights, LGBT rights, Bernie—have different roots, structures, and foci, but they share a recognition that we are being crushed by the newest form of capitalism—as they call it in Latin America, “capitalismo salvaje”1 (savage capitalism)—and that we must stand up to it with all our might, with all our people.

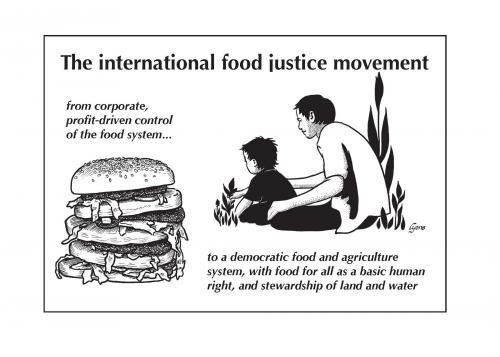

A movement with enormous potential to contribute to this process is the food justice movement. Often led by low-income people of color and linked to global food sovereignty struggles, it not only offers a radical analysis but it is increasingly influencing the less-politicized food movement that is focused on healthy eating, community gardening, and community supported agriculture (CSAs). The food justice movement is creating alliances; is supporting leadership from people of color, youth, and working people; and can be a critical element in building a truly mass-based movement.

The broadest context of the food movement is global: It is an enormous mass movement of the poor, led by people of color, supportive of women and youth, and anti-capitalist. In the United States the radical wing of the food movement, calling itself food justice, mirrors the global: It likewise is led by people of color, is anti-capitalist, and is dominated by women and youth. That U.S. radical wing exerts a dynamic pull to the left on the more moderate “do-good” food movement—food pantries, CSAs—as capitalism narrows opportunities, and suffering increases.

Mapping Out the Movements

Since so much of U.S. agriculture has long been corporatized, with family farms going out of existence at a fast clip and only 1-2 percent of the population engaged in commercial cultivation, the United States faces particular challenges in organizing on food issues.

The variegated branches of the food movement in the United States are here divided into two: “food movement” (reformers addressing health, hunger, entrepreneurship, flavor, and food safety issues), and “food justice” (farmers, progressive farmer advocates, and activists seeking equity and sustainability through structural changes). Both strands encompass great diversity of approaches and have a great deal of overlap.

U.S. Food Movement

The U.S. food movement, or what some people call the “good food movement,” does not necessarily see itself as a movement. Many of its participants are attracted by the concrete projects and activities that provide a sense of accomplishment and community. The movement is a set of organizations that coalesce, mostly on local levels, around shared interests such as health and ending hunger. While nationally these kinds of organizations often separate when the going gets tough, for instance when federal legislation pits “enough” food against “healthier” food, local representatives and organizations tend to be able to bridge that binary more congenially.2 While most of the central players are nonprofit or government professionals, hundreds of thousands of people across the United States participate, mostly without much power or influence, as volunteers in food pantries, diet and exercise programs, and often in community gardens.

The problems they confront are enormous: More than 50 million Americans, one in six, are “food insecure,” meaning they are unable to rely on adequate, regular food, and half of these are children. About half the U.S. adult population and 1/3 of children are overweight or obese, many of them low-income and people of color. Programs like First Lady Michelle Obama’s “Let’s Move,” almost completely fueled by volunteers, have had limited traction in the communities that need them the most, particularly as corporations have managed to water them down.3 Beverage companies like Coca-Cola deny the role of sugar and pay for research that “proves” the centrality of exercise for combatting obesity.4 The army of well-meaning but often non-politicized volunteers is no match for these transnational corporations, though many well-meaning people are kept very busy on a single issue within a moral and civic framework.5

Some dedicated food pantry workers and volunteers see the need for a broader approach to deal with hunger, beyond distributing food. The Stop, in Toronto, provides a rich model of such a multiservice organization focused on food security.6 Many participants at the “Closing the Hunger Gap” Conference in 2015 challenged the traditional single-issue, hunger-only politics, making the event groundbreaking as it shifted to a more holistic, anti-poverty, multiservice, coalition-building stance.7 Bed-Stuy Campaign Against Hunger in Brooklyn, New York, is one such organization. Started as a faith-based food pantry, it has expanded into an anti-poverty organization offering a wide range of services including public assistance, development of several sizable gardens, job placement, and housing advice.

Child and school food advocates have a strong national presence, framed around fighting poverty. One of the largest, Food Research and Action Center, works primarily on the U.S. federal budget, child nutrition legislation, and agricultural programs geared toward school lunches, summer nutrition programs, and after-school programs. Parents and community groups committed to improving school food quality have brought an energy and policy focus to the food movement. While grassroots in much of their orientation, policy work is centralized, much of it led by nonprofit organizations such as School Food Focus and Wellness in the Schools. Youth groups dedicated to cooking and growing food add to these grassroots voices.

Successes have been significant. The Los Angeles Unified School District now procures most of its food locally through a program developed by the nonprofit Los Angeles Food Policy Council. Procurement is evaluated on five values: proximity, sustainability, valued workforce, animal rights, and nutrition. Due to extensive pressure by parents and food advocates, the New York City school system now has a universal free-food system in place for all middle schoolers and has committed to dramatically expanding locally sourced foods. Advocates are hoping to expand both programs system-wide.8

The “food movement” also is populated by “foodies” and gardeners, sometimes conflated and other times distinguishing themselves from each other. “Foodies” generally want healthy, local, delicious food, focusing on freshness and pleasure and supporting a culture of change around cooking, eating, dining out, and supporting local farmers. As with other groups a huge range exists within this sector; it is varied in race, class, gender, and region. Slow Food is the most emblematic organization, though thousands of other, smaller groups, from supper clubs to home, faith organizations or community gardeners contribute. Collectively they often change the demand side of the food economy equation, thus supporting an increase in small-scale operators on the supply side. This includes small-scale and local farmers, the burgeoning farmers markets, food cooperatives, new small “healthy food” businesses, sustainable restaurants, and student groups improving their school cafeterias. This local, small-scale capitalism can create a deep sense of community.

Community Supported Agriculture groups (CSAs) are great examples of this. They create a direct relationship between a group of urban dwellers (consumers), usually defined by a neighborhood, with a local farmer (producer) and distribute food to the members of the CSA based on what is actually produced by the farmer. The farmer gets cash up front, decreasing the need for loans; the consumer gets fresh, usually organic, produce. CSAs often create cooperative structures for dividing up the work that the food distribution requires.9 These sorts of community-building efforts reduce the isolation associated with urban life.

Community gardens operate on the same principle. Land is either totally shared and cooperatively worked or divided into small plots, and community gardeners join together to arrange work schedules and to celebrate the harvest. These efforts can convey to participants that life can function well outside of corporate control. But too often, these groups don’t incorporate strategies to transform the huge inequities in the food system.

U.S. Food Justice Movement

While their projects frequently look similar, food justice movement activists are more likely than people who focus on food access to frame and organize around specific principles of justice, allowing a closer connection with international movements. The United States Food Sovereignty Alliance (USFSA), made up of 36 groups, and the National Family Farm Coalition (NFFC) are the two main U.S. organizations that are connected globally. They are both coalitions of member organizations. USFSA is a larger, more expansive alliance that includes food justice, anti-hunger, labor, environmental, faith-based, and food producer groups. It works toward sustainable local agricultural systems connecting local and national struggles to the international movement for food sovereignty.10

NFFC has a longer history, alliances with other national and global food-related policy groups, and members that are long-standing professional farmer organizations, including small- and medium-sized cooperatives of farmers. As an active member of USFSA, NFFC works toward a democratic food and agriculture system that ensures health, justice, and dignity and emphasizes policies that support local and smaller scale agriculture.11 Both groups are racially integrated and share deep respect for and commitment to leadership of people of color, especially indigenous groups. Both are internationalist in their understandings and are grassroots and democratic in their structures and commitments.

A recent campaign offers a glimpse of how these two groups work together. The United Nations announced 2016 as the Year of People of African Descent. Activists from NFFC and USFSA are joining together to use UN hearings scheduled in various parts of the United States to explain food sovereignty to their peers. They will talk about how land has been taken from Americans of African descent in the past and how today that continues to impoverish African Americans.12

“Sovereignty,” a term used broadly in the Global South,13 is not a familiar term for most people in the United States; “justice” is a more commonly used framework. Race, indigeneity, and inequality in terms of resources, opportunities, and control, including within organizations and alliances, are all important issues in food justice. While class and corporate control are both central to the analysis, “capitalism” as a system is not often directly addressed.14

The Food Chain Workers Alliance (FCWA, foodchainworkers.org), with 27 member groups and itself a member of the USFSA, advances the power and conditions of food workers, who are among the lowest paid. Within a democratically controlled member-organizational model, they address the intersection of labor, sustainability, and climate and stress working in coalitions.

Their best-known members include the tomato pickers in the Coalition of Immokalee Workers (ww.ciw-online.org) and the Fight for $15 fast food workers (fightfor15.org). In 2015 the FCWA created the HEAL Food Alliance—Health, Environment, Agriculture, and Labor—along with their allies: the Real Food Challenge (campus food organizing), Union of Concerned Scientists, and the Movement Strategy Center. They are working to develop a “Real Food Platform” that identifies corporate control of the food system as its primary target.

The Detroit Black Community Food Security Network (detroitblackfoodsecurity.org) is another member of the USFSA. Framing their work in race and class, they represent a broad group of urban farmers growing food for themselves and for sale as well, creating greater access and self-sufficiency in their communities. A specifically grassroots-controlled organization, they have been the prime movers behind establishing the Detroit Food Policy Council that works with government and community to advance legislation to improve food security and access. They are developing a food cooperative to fill the food desert created as Detroit lost population, income, and white residents. Malik Yakini, co-founder and executive director, indicates, “In our organization we try to connect the day-to-day work to challenge capitalism and white supremacy. We see food as an entry point into this larger analysis, the same system that makes food insecurity makes war, structural racism, disinvestment, sexism.”15

The Global Food

Sovereignty Movement

The U.S. food justice movement is also to varying degrees connected to the global food sovereignty movement. Peasant organizations across the Global South and parts of the Global North have long been organizing to save their land from corporate land grabbers;16 protect their water resources; keep control over the foods they produce and the communities they serve; maintain sustainable growing, processing, and distribution practices; and influence government policies that affect their lives.

Since its 1993 founding, La Via Campesina (LVC) has become the world’s largest social movement, representing 200 million farmers from 73 countries in an autonomous movement independent from any political, economic, or other type of affiliation.17 It brings together peasants, small- and medium-scale farmers, landless people, women farmers, indigenous peoples, fisher folks, pastoralists, migrants, and agricultural workers from around the world. Its focus is on defending small-scale sustainable agriculture in order to promote social justice and dignity.

Many LVC groups are deeply engaged in working for land redistribution, as conscious stewards of the land and water; others work collectively in small-scale cooperatives and rural land-seizure-based communities. They are frontline defenders of their land and water against extractive industries, mostly owned by transnational conglomerates.18 Ibrahima Coulibaly, president of the National Coordination of Peasant Organizations of Mali, notes, “Only agroecological peasant production can disconnect the price of food from financial speculation and from market distortions, restore land degraded and polluted by industrial agriculture, and produce local and healthy food for urban consumers and for our people in general.”19

Most peasant movements consist of people of color; many are led by women or have women in second- and third-level leadership positions. Women are most often the actual cultivators. In the Tamil Nadu Women’s Collective in India, with more than 100,000 women farmers, leadership roles, strategies, and tactics are fully determined by women. They have a busy annual calendar of grassroots community organizing, demonstrations, direct actions, media appearances, and planning sessions. They organize in groups of ten women, sharing loans, seeds, labor, and stories.

Nonetheless, people’s struggles around food sovereignty in the Global South often remain disconnected. In recent travels in Latin America, one of us met many peasant and urban cultivators who had never heard of the movement for food sovereignty or of LVC. Yet they are solving their shared problems with their counterparts all over the world in similar ways: building communities of cultivators; sharing seeds and labor; resisting land grabs, extractive industries, and gentrification; and serving their communities.

Connecting the Dots: Progressive

Shifts in the Food Movement

WhyHunger, a national organization that links to global food sovereignty efforts, has networked food pantries nationally into its Grassroots Action Network. WhyHunger has recently adopted the stance that the right to food is a basic human right, thus connecting it to global groups that use the same terminology.20 Beatriz Beckford, director of WhyHunger’s Growing Grassroots Power program, sees a steady shift in the food movement from its early “healthy food access” period to a much more radical set of coalitions, projects, and campaigns that address race, gender, and environmental issues. She notes the shift away from the narrative of “personal choice” to the critiquing of the profit-driven food system. Beckford sees the next stage of the food justice movement as confronting state and corporate entities through movement building and direct action. She “connects the corporate food system, stealing of land from Black people, block busting, redlining, mass incarceration, and death of Black people by the state as ways in which the state has controlled Black bodies.” She is hopeful that this analysis and the movements that express it will expand over the next few years.21

Another example of this shift is found in New York City’s Just Food which started as a network of CSAs providing popular education around food and now “empowers and supports community leaders to advocate for and increase access to healthy, locally grown food, especially in underserved New York City neighborhoods.” Their recent shift to include climate, race, and gender issues shows the effects of this general change among food activists toward a more holistic and systemic approach.

Ceding to pressure from urban agriculture groups, the State of California recently passed the Neighborhood Food Act, AB 2561. The act grants people “the right to grow food for themselves regardless of their housing status,” guaranteeing to tenants and members of homeowners’ associations the right to grow food for personal consumption by voiding contrary language in existing leases or homeowners’ association agreements.22 While this is a reform, it is based in a “rights” paradigm, not just on ensuring access to healthy foods. This has the potential to make a small but significant structural change that can contribute to changing power dynamics in California.

The food justice movement is increasingly connected with other progressive U.S. movements. Diana Robinson, campaign and education coordinator of FCWA, has seen a shift in the food justice movement over the last ten years. “The movement has created unusual bedfellows: climate, unions, community,” she says. “More organizations are talking about race. There is support in the food justice movement for Black Lives Matter and for the climate justice movements. People of color are leading those efforts because these are the issues they experience in their everyday lives. We now have more of a shared vision of how we want to change the food system. People are a lot braver. I’m excited!”23

Living on grant money often restricts democratic participation and “movement politics.”24 The organizations that define and lead much of the mainstream food movement in the United States are rarely democratically structured. Most are organized as nonprofits with projects that are chosen by boards of directors, usually appointed rather than elected by constituents.25 Staff members who have direct relationships with constituents most often have little freedom to veer away from decisions and plans made by their boards. Staff are usually overworked and underpaid due to underfunding of nonprofits, and organizational plans are usually geared toward foundation preferences.

This is a dilemma that most staff-driven organizations face: balancing service-oriented work that pays the bills against growing a political movement. When democratic decision-making holds sway, movement building is more likely but still not necessarily a focus. Many participants in small-scale, grassroots projects shy away from public policy, joining broader coalitions, or participating in direct actions and mobilizations.26

There are exceptions of course. The New York City Community Garden Coalition, representing more than 800 community gardens and thousands of gardeners, is on the streets, at demonstrations, at public hearings, and in broader political coalitions. They struggle constantly with the New York real estate industry, which has received substantial tax breaks to build housing, with some “affordable” units, on publicly owned land, often land that has existing community gardens.

NYCCGC has only one half-time staff member, no office, and a board of directors elected directly by the members. They link the global phenomenon of “land grabs” in the Global South to those in the South Bronx and Brooklyn. They see community gardens as part of the “commons” that the city is trying to ”enclose,” as occurred in England in the eighteenth century, creating private wealth at the expense of public use.27 While the community garden coalition began decades ago as a “food movement” group without a critical analysis of capitalism and land, the NYCCGC now falls squarely in the food justice/food sovereignty domain. The coalition’s work as part of the People’s Climate Movement-NY further connects it to a system-change perspective.

The hope is that projects like these, with strong ties to both the broader food movement and to the food justice movement, will expand and serve as bridges to pull more food movement participants into struggles for social and economic justice. As the crises of capitalism deepen—with increased climate change, inequality, and corporate control—more radical solutions will be sought, both left and right. With the leftward tug of the U.S. food justice movement and the global framework of the food sovereignty movement, the broader food movement is likely to move in a more progressive direction. The potential is certainly there.

Footnotes

Notes

1. Gerardo Renique, “Subaltern Political Formation and the Struggle for Autonomy in Oaxaca,” Socialism and Democracy (21, 2007), 62-73.

2. Personal communication with Nicholas Freudenberg, distinguished professor of public health and director of the New York City Center for Food Policy.

3. Aviva Shen, "How Big Food Corporations Watered Down Michelle Obama’s ‘Let’s Move’ Campaign," Think Progress, February 28, 2013.

4. Marion Nestle, Soda Politics: Taking on Big Soda (And Winning) (Oxford University Press, 2015).

5. Janet Poppendieck, Sweet Charity: Emergency Food and the End of Entitlement (Penguin, 1998).

6. Nick Saul and Andrea Curtis, The Stop: How the Fight for Good Food Transformed a Community and Inspired a Movement (Melville House, 2013).

7. Erik Talkin blog, “Hippie Banking of the Future of Food Banking,” Oct. 6, 2015.

8. Community Food Advocates NYC.

9. Elizabeth Henderson, Sharing the Harvest: A Citizen’s Guide to Community Supported Agriculture (White River Junction, VT: Chelsea Green Publishing, 2007).

10. usfoodsovereigntyalliance.org, founded in 2010.

11. nffc.net, founded in 1986.

12. Pigford v. Glickman, 2007, www.blackfarmercase.com.

13. The Global South has about 85 percent of the total world population, and more than 4 billion people live in rural areas, most of whom are peasant cultivators and other small-scale food producers.

14. Eric Holt-Gimenez, ed., Food Movements Unite! (Food First Books, 2011). Fred Magdoff and Brian Tokar, eds., Agriculture and Food in Crisis: Conflict, Resistance, and Renewal (Monthly Review Press, 2010).

15. Personal communication, Dec. 20, 2015.

16. “In the past decade, more than 81 million acres of land worldwide—an area the size of Portugal—has been sold off to foreign investors. Some of these deals are what’s known as land grabs: land deals that happen without the free, prior, and informed consent of communities.” Oxfamamerica.org.

17. Via Campesina.

18. Joao Pedro Stedile and Horacio Martins de Carvalho, “People Need Food Sovereignty,” in Eric Holt-Gimenez, ed., Food Movements Unite! (Food First Books, 2011).

19. Ibrahima Coulibaly, “Why We need Agroecology,” Why Hunger.

20. Right to Food Campaign.

21. Personal communication, Dec. 20, 2015.

22. "California Passes Neighborhood Food Act," Insteading.

23. Personal communication, Dec. 20, 2015.

24. Francis Fox Piven and Richard Cloward, Poor People’s Movements: Why They Succeed and Why They Fail (Vintage, 1979).

25. Joan Roelofs, "A Critique of Non-Profits," Socialist Action, December 23, 2007.

26. Incite! Women of Color Against Violence (eds.), The Revolution Will Not Be Funded Anthology (South End Press, 2007), www.incite-national.org.

27. Ray Figeroa-Reyes, president of the New York City Community Garden Coalition, personal communication, Dec., 2015.

Leave a Reply