Seventy years ago, Victor Serge put the finishing touches on his masterpiece — Memoirs of a Revolutionary: 1903-1941 — which he (correctly) considered “unpublishable” in his lifetime. On February 28, 1943 he wrote the following entry in one of his Carnets (Notebooks), which recently came to light in Mexico and were published for the first time in France in 2012.[1]

Souvenirs

“Jeannine’s birthday.[2] Finished Souvenirs, which I will probably entitle Souvenirs of Vanished Worlds in the French edition… What is left of those worlds which I have known, where I have struggled? France before the First War, the war, victory, Spain, where the revolutionary fermenting was rising so powerfully, the Europe of ‘birth of our power,’[3] Russia during the great epic years, the Europe of boundless hopes, Germany and Austria at indecisive crossroads, the Russian Thermidor, the West of popular fronts? Nothing of these worlds will ever be reborn; we are being launched at top speed toward something new, through disasters, toward unforeseeable rebirths or toward long dusks, which at times will resemble rebirths… And how many dead left behind me on all those paths! Three or four generations of comrades…

The book is finished; I’m at an impasse. Is it publishable? It is dense, a difficult read, for I wanted to make of it a precise and thought out testimony, not the emotional adventure of Me, which is what it would have taken to write a ‘best-seller’ [Serge’s English]. But that’s not its real defect: it accuses the Stalinist regime, pitilessly objectively, even more than my novel [The Case of Comrade Tulayev[4]] deemed ‘unpublishable at this time’ in New York by virtue of an ‘unwritten law,’ as one publisher put it, which forbids criticizing Russian despotism, ‘our ally.’ [Serge’s English]. Thus, the more a book is intense, rich, irrefutable, and the better it pokes its finger in the wound from which the universe is suffering, the less chance it has of being published. This will probably change, and perhaps soon, but how to live counting on this soon which could contain an epoch when every semester carries its weight of rent and daily bread?

“At times the crushing feeling of an impasse closed at both ends. It’s no longer an impasse; it’s a vast prison yard. No way to get an article into an American magazine (same reasons, and my name scares them), two great unpublishable books, crying out with truth — no possibility of finding work here. I tell myself that I must struggle while adapting myself, write in half-tones, avoid dealing with problems where the least mot juste acts like salt on a wound, that there are still ways, under these conditions, to pose the human question; but at times I feel a heavy discouragement … The way things are going, won’t my very signature be a handicap to my writings, even if I succeed — it will be difficult — of putting in them a mere murmur of what ought to be shouted from the rooftops?

If I were younger — more muscular force — I would wait it out, working at any trade that brings in the bacon. But I have nothing left in sum but a brain, which nobody needs at this moment and which many would prefer to see pierced by a small definitive bullet.”

Victor Serge’s Political Testament

What would Victor Serge’s political position be if he were alive today? During the 60-odd years since Serge’s untimely death, this question — a priori unanswerable — has been asked (and answered) many times — on occasion, as we shall see, by self-interested politicos and pundits. The consensus among these postmortem prophets is that this hypothetical posthumous Serge would have moved Right, along with ex-Communists like Arthur Koestler and the N.Y. Intellectuals around the Partisan Review. It is of course, impossible to prove otherwise, but the fact remains that throughout the Cold War neither the CIA-sponsored Congress for Cultural Freedom nor any other conservative anti-Communist group ever attempted to exploit Serge’s writings, which continued to speak far too revolutionary a language and remained largely out of print. Nonetheless, the specter of an undead Right-wing Serge continues to haunt the critics, and there are reasons why.

To begin with, in January 1948, a month after Serge’s death, that great confabulator André Malraux launched a macabre press campaign claiming Serge as a deathbed convert to Gaullism.[7] The sad fact is that six days before he died, Serge had sent a grossly flattering personal letter to Malraux, begging the support of de Gaulle’s once and future Minister of Culture (and Gallimard editor) to publish his novel Les Derniers temps in France.[8] Desperate to leave the political isolation and (fatally) unhealthy altitude of Mexico for Paris, Serge indulged in an uncharacteristic ruse de guerre, feigning sympathy for Malraux’s “political position” — according to Vlady, at his urging. Serge’s ruse backfired. His letter and the news of his death reached Paris simultaneously, and Malraux seized the moment by printing selected excerpts and leaking them to C.L. Sulzberger, who published them in the N.Y. Times — thus recruiting Serge’s fresh corpse into the ranks of the Western anti-Communist crusade.[9]

Aside from this letter, there is zero evidence in Serge’s writings, published and unpublished,[10] of sympathy for Gaullism or Western anti-Communism — quite the contrary. In 1946, Serge sharply criticized his comrade René Lefeuvre, editor of the far-left review Masses, for publishing an attack on the USSR by an American anti-Communist: “If the Soviet regime is to be criticized,” wrote Serge, “let it be from a socialist and working‑class point of view. If we must let American voices be heard, let them be those of sincere democrats and friends of peace, and not chauvinistic demagogues; let them be those of the workers who will succeed one day, we hope, in organizing themselves into an independent party.” A few months later, Serge followed up: “I understand that the Stalinist danger alarms you. But it must not make us lose sight of our overall view. We must not play into the hands of an anti-Communist bloc […] We shall get nowhere if we seem more preoccupied with criticizing Stalinism than with defending the working class. The reactionary danger is still there, and in practice we shall often have to act alongside the Communists.”[11]

To complicate matters even further, in the course of a fraternal discussion with Leon Trotsky over Kronstadt and the Cheka in 1938, the “Old Man” unjustly (on the basis of an article he hadn’t read),[12] portrayed Serge as abandoning Marxism along with Stalinism and drifting to the Right.[13] Nonetheless Serge, despite political differences of which the reader of these Memoirs is aware, continued to defend Trotsky to his death, helped expose Trotsky’s murderer, and collaborated with Trotsky’s widow, Natalia Sedova, on The Life and Death of Leon Trotsky. Yet generations of Trotskyists have reflexively handed down Trotsky’s caricature of Serge as a ‘bridge from revolution to reaction’ — an accusation apparently confirmed by the “Gaullism” charge.

More recently Serge’s posthumous rightward drift has been alleged on the basis of his guilt-by-association with erstwhile U.S. leftists and socialists who subsequently moved Right. (Of course Serge’s main political associations were in Europe, a fact this argument ignores.) One recalls that in Mexico Serge lived by his pen (like Marx in exile who wrote for Greeley’s N.Y. Tribune) writing news articles in English for the Social-Democratic press (the staunchly anti-Communist Call and New Leader) as well as think pieces for the Partisan Review (whose editors had supported his struggles to survive in Vichy France and Mexico). Many of these N.Y. Intellectuals did indeed move rightward, beginning with James Burnham in the 1940s. Thus Serge, it is argued, “would have” moved Right too. Yet, not long before he died, Serge vigorously attacked Burnham, writing: “The paradox that he has developed, doubtless out of love for a provocative theory, is as false as it is dangerous. Under a thousand insipid forms it is to be found in the Press and the literature of this age of preparation for the Third World War. The reactionaries have an obvious interest in confounding Stalinist totalitarianism — exterminator of the Bolsheviks — with Bolshevism itself; their aim is to strike at the working class, at Socialism, at Marxism, even at Liberalism…”

All this would be just a sad footnote were it not that the posthumous image of a right-wing Serge, based on the old Gaullism and NY Intellectualism arguments, was still being agitated as late as 2010.[14] To lay this ghost once and for all, let us quote Serge’s last significant political statement, generally considered his “political testament.”

Thirty Years After the Russian Revolution was dated August 1947 and published in Paris by La Révolution proletarianne in November 1947, the month of his death.[ ]There Serge writes: “A feeble logic — pointing an accusing finger at the dark spectacle of the Stalinist Soviet Union — deduces from this the bankruptcy of Bolshevism, hence that of Marxism, hence that of Socialism […] Aren’t you forgetting the other bankruptcies? Where was Christianity during the recent social catastrophes? What happened to Liberalism? What did Conservatism — enlightened or reactionary — produce? Did it not give us Mussolini, Hitler, Salazar, and Franco? If it were a question of honestly weighing the many failures of different ideologies, we would have our work cut out for us for a long time. And it is far from over …”

As far as capitalism is concerned, Serge concluded:

"There is no longer any doubt that the era of stable, growing, relatively pacific capitalism came to an end with the First World War. The Marxist revolutionaries who announced the opening of a global revolutionary era—and another period of barbarism and a “cycle of war and revolution” (as Lenin put it, quoting Engels) would follow — were right. The conservatives, the evolutionists, and the reformists who chose to believe in the future bourgeois Europe carefully cut into pieces at Versailles, then replastered at Locarno, and fed with phrases dug up at the League of Nations — are today remembered as statesmen of blind policies….

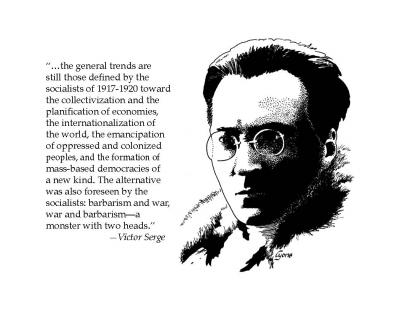

"The Marxist revolutionaries of the Bolshevik school awaited and worked toward the social transformation of Europe and the world by an awakening of the working masses and by the rational and equitable time when men would take control over their own destinies. There they made a mistake — they were beaten. Instead, the transformation of the world is taking place amidst a terrible confusion of institutions, movements and beliefs without the hoped-for clarity of vision, without a sense of renewed humanism, and in a way that now imperils all the values and hopes of men. Nevertheless the general trends are still those defined by the socialists of 1917-1920 toward the collectivization and the planification of economies, the internationalization of the world, the emancipation of oppressed and colonized peoples, and the formation of mass-based democracies of a new kind. The alternative was also foreseen by the socialists: barbarism and war, war and barbarism — a monster with two heads."

As Peter Sedgwick put it in 1963: “Whatever else they may be, these are not the words of a man of the Right, or of any variety of ex-revolutionary penitent.”

About the 2012 Translation

of Serge’s Memoirs

This is the first complete, unexpurgated edition of Victor Serge’s classic to be published in English (Memoirs of a Revolutionary, NYRB Classics Edition), and thereby hangs a tale. Translating Serge has ever been a labor of love (and of political commitment), and this was especially true for Peter Sedgwick, who undertook to translate into English the Memoirs in the early 1960s when Serge was an all-but-forgotten figure. Sedgwick (1934-1983) was an English psychologist (and later politics lecturer) author of highly original works on politics and psychology and well known for his vast erudition, pungent wit, and personal modesty (see www.petersedgwick.org). Sedgwick had a difficult childhood during WWII, became a Christian Socialist as a youth, then a member of the Communist Party until the Soviet invasion of Hungary in 1956. Leaving the CP, Peter was a founding member of what became the New Left in Britain — first within the Socialist Review Group, then the International Socialism Group. After graduating from Oxford, where he had been a scholarship student at Balliol College, Peter began translating the Memoirs for Oxford University Press in whatever spare time he had left over from raising two young children, while eking out an uncomfortable living as a tutor organizer in Her Majesty’s prison at Grendon Underwood, where I first met him.

It took Sedgwick years to complete this heroic project, to which he brought scrupulous fidelity to Serge’s French, a vast (and indispensable) knowledge of revolutionary history and politics, a wry sense of humor and a vigorous English style which well-suited Serge’s passionate laconism. So I was shocked when Peter informed me in 1963 that Oxford University Press had told him that as a condition of publication his translation had to be shortened by one-eighth — an economy measure![5] So with heavy heart, Peter expurgated his translation, making nearly 200 separate cuts so as to preserve as much as possible the coherence of Serge’s dense, highly compressed narrative.

Today, thanks to a Greek socialist and Serge fan, we have an integral version of Serge’s original text. In 2007, George Paizis (former senior lecturer in the Department of French at University College London and a longstanding member of the Socialist Workers Party) volunteered to go painstakingly through the French and English texts, identify the deleted sections, and translate them anew. Hence this first unexpurgated edition, which includes Peter Sedgwick’s seminal Translator’s Introduction, Adam Hochschild’s eloquent post-Soviet Foreword, and a Glossary of revolutionaries and institutions mentioned by Serge (first occurrence indicated by an asterisk).[.]

Since the 30s, Serge has been well-served by his volunteer corps of English translators, mostly Marxist militants with a love of French and French literature, from U.S. Trotskyist leader Max Shachtman (and sympathizer Ralph Manheim) to the late Al Richardson of Revolutionary History in London (who collected and translated all of Serge’s Writings on Literature and Revolution in 2004) and Ian Birchall, revolutionary socialist writer and activist who gathered and translated Serge’s reportage on revolution and counter-revolution in Russia and Germany.

French novelist François Maspero, whose leftist publishing house revived Serge’s books (all but forgotten in post-war France) in the rebellious 60s, recently remarked: “There exists a sort of secret international, perpetuating itself from one generation to the next, of admirers who read, reread [Serge’s] books and know a lot about him.” As Adam Hochschild notes in his Foreword, “It is rare when a writer inspires instant brotherhood among strangers.”

Back in 1963 when, inspired by Serge’s artist son Vlady[6], I began translating Serge’s novels and looking for a U.S. publisher, this “secret international” came to my aid, with letters of support. Dwight Macdonald, who with his wife Nancy,* had worked tirelessly to rescue Serge from Vichy France, replied: “I can’t think of anyone else who has written about the revolutionary movement in this century with Serge’s combination of moral insight and intellectual richness.” Irving Howe, whose YPSL reading list first pointed me to Serge replied: “To me he has seemed a model of the independent intellectual in Europe between the wars: leftist but not dogmatic, political, yet deeply involved with issues of cultural life, and a novelist of very considerable powers.” The urbane Henri Peyre, my old French professor from Yale, replied offhandedly: “Victor Serge is as worthy of a study by a scholar interested in ideas as is Proudhon, Georges Sorel or Charles Péguy. And he certainly counts also as a novelist — to me, far more than most of the 18th century novels which have been ridiculously overrated lately, and more than Robbe-Grillet and his vapid, skilled fiction and, may I confess, more than Beckett.”

Erich Fromm, who had known Serge in the Forties through psychoanalytical circles in Mexico (and whom our student socialist club had to Yale in 1961) replied: “I believe indeed that to rescue the humanist tradition of the last decades is of the utmost importance, and that Victor Serge is one of the outstanding personalities representing the socialist aspect of humanism.” The journalist I.F. Stone from whom I had “borrowed” my first Serge book wrote:

"Victor Serge died in exile and obscurity, apparently no more than a splinter of a splinter in the Marxist movement. But with the passage of the years, he looms up as one of the great moral figures of our time, an artist of such integrity and a revolutionary of such purity as to overshadow those who achieved fame and power. His failure was his success. I know of no participant in Russia’s revolution and Spain’s agonies who more deserves the attention of our concerned youth."

Bertram D. Wolf, whose Three Who Made a Revolution had inspired me as a teenager, wrote “Serge’s writing was simple, vivid, strong, written with an insider’s knowledge, the insights of a passionate yet detached observer and participant, and the skill of a poet and novelist.” For Trotsky biographer Isaac Deutcher: “The Case of Comrade Tulayev is by far the best novel about the period of the purges — far richer artistically and more truthful historically than Koestler’s famous book.”

These endorsements, which date from 1964, confirmed my judgment that Serge was indeed a major figure in both literature and socialist thought. The Doubleday project was successful, and my 1960s translations of Men in Prison, Birth of Our Power, and Conquered City were reprinted in Britain by Gollanz and then Penguin in Britain. In the Eighties the Writers & Readers Publishing Coop in London bought the rights to the trilogy and commissioned me to translate into English a fourth Serge novel, Midnight in the Century.* My latest Serge translation of the posthumous novel Unforgiving Years, commissioned by NYRB Classics, came out in 2008.

With the publication of the unexpurgated Memoirs, and on behalf of all of Serge’s translators, it was a keen pleasure (and revolutionary duty) to welcome new readers into an English-language section of this invisible international.

Footnotes

1. Serge, Carnets, Agone, Marseille, 2012.

2. Serge’s daughter Jeanine Kibalchick (1935-2012).

3. Allusion to Serge’s 1931 novel, Birth of Our Power.

4. NYRB Classics, 2008, Preface by Susan Sontag.

5. Born on the winds of the New Left 60s, Oxford’s truncated Memoirs of a Revolutionary quickly became a minor classic, reprinted in the 80s by the radical Writers & Readers Publishing Cooperative and again in 2002 by Iowa University Press.

6. See www.Vlady.org.

7. Peter Sedgwick analyzed this incident in detail in “Victor Serge and Gaullism,” appended to the original 1963 Oxford Memoirs on which we have in part based our summary.

8. The topic of Serge’s novel occupies two thirds of the original typescript letter, a photocopy which was made available to me in 1990 by Florence Malraux, the writer’s daughter.

9. ‘Europe’s Anti-Red Trend Inspiring Strange Tie-Ups.’ Subtitle : “New Coalitions Courting Leftist Support to Bring Workers Into Pale” by C.L. Sulzberger, NYT February 14, 1948.

10. Serge Archive, Yale University Library.

11. Quoted from Ian Birchall, “Letters from Victor Serge to René Lefeuvre,” Revolutionary History, Volume 8 No 3 (2002).

12. “Marxism in Our Time” by Victor Serge, Partisan Review Vol. 5, No. 3. Aug.-Sept. 1938, pp. 26-32.

13. See “Opposition Within the Opposition Victor Serge and Leon Trotsky — Relations 1936-1940” in Beware of Vegetarian Sharks by Richard Greeman.

14. Cf. “Orphan of History” by James Hoberman, NYRB, Oct. 22, 2010.

Leave a Reply